National Judicial Appointments Commission

2022 DEC 12

Mains >

Polity > Judiciary > Judicial Appointments

IN NEWS:

- A private member bill to regulate the appointment of judges through the National Judicial Commission was recently introduced in Rajya Sabha. The National Judicial Commission Bill, 2022, was introduced after the majority of voice votes were in its favour.

- In his maiden speech as the chairman of the Rajya Sabha on the first day of the winter session of parliament, Vice-President Jagdeep Dhankhar chided the two Houses for not taking cognisance of the 2015 Supreme Court judgment setting aside the Constitutional amendment to constitute the National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC).

APPOINTMENT OF JUDGES- WHAT THE CONSTITUTION SAYS:

- Articles 124 and 217 of the Constitution deals with the appointment of judges of the higher judiciary.

- They state that the President appoints the Chief Justice and the judges of Supreme Court and high courts, after appropriate consultations.

- The chief justice is appointed by the President after consultation with such judges of the Supreme Court and high courts as he deems necessary.

- The other judges are appointed by president after consultation with the chief justice and such other judges of the Supreme Court and the high courts as he deems necessary.

- The consultation with the chief justice is obligatory in the case of appointment of a judge other than Chief justice.

EVOLUTION OF COLLEGIUM SYSTEM:

- The Supreme Court has given different interpretation of the word ‘consultation’, which eventually led to the formation of the collegium system.

- In the First Judges case (1982), the Court held that consultation does not mean concurrence and it only implies exchange of views.

- But, in the Second Judges case (1993), the Court reversed its earlier ruling and changed the meaning of the word consultation to concurrence. It ruled that the advice tendered by the Chief Justice of India on the matter is binding on the President. But the Chief Justice would tender his advice on the matter after consulting two of his senior-most colleagues.

- In the Third Judges case (1998), the Court opined that the consultation process requires ‘consultation of plurality judges.’

- He should consult a collegium of four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

- Even if two judges give an adverse opinion, he should not send the recommendation to the government.

FUNCTIONING OF THE COLLEGIUM SYSTEM:

- The collegium is involved in the appointment as well as the transfers of judges.

- The Collegium sends their recommendations of the names of lawyers/judges to the Central Government. Similarly, the Central Government also sends some of its proposed names to the Collegium.

- The Central Government does the fact checking and investigate the names and resends the file to the Collegium.

- Collegium considers the names or suggestions made by the Central Government and resends the file to the government for final approval. If the Collegium resends the same name again then the government has to give its assent to the names.

- If there is any dissent within the collegium, the CJI should communicate such dissenting view, along with the recommendation, to the government. If there is a dissent in the collegium regarding a recommendation, the government can ask the collegium to reconsider it.

ISSUES WITH COLLEGIUM SYSTEM:

- Invention by the judiciary:

- The system is outside the constitutional scope, as it is an invention of the judiciary. The constitution makers had no intention to give primacy to the CJI, which is why it was made necessary to only consult him than concur with him.

- Undemocratic:

- The collegium system is undemocratic as the people’s representative have no say in it. The whole power is monopolized in the hands of a few. In fact, India is the only country where judges appoint judges.

- Opaque selection process:

- Since 2017, the collegium has been voluntarily publishing its various decision, along with the reasons underpinning the collegium’s choices. However, this was not followed in 2019 when it publishes appointment details without reasons. This leaves many aspects, such as how the criteria like work, reputation, integrity and experience play in the selection process, beyond scrutiny.

- Lack of accountability:

- Most of the collegium functions are outside the ambit of RTI. There is no written manual for functioning or definite selection criteria. Also, the decisions already taken are often arbitrarily reversed. It has even taken decisions against its own guidelines without proper explanations.

- Eg: In January 2019, the court superseded 3 senior-most judges while recommending names for elevation to the Supreme Court, abandoning the guideline of respecting seniority in appointments.

- Arbitrariness in actions:

- There are instances where some judges are transferred for unknown reasons as a punishment. Also, as there is no age criteria for becoming judges, some are rejected for want of age while some are appointed overnight.

- Eg: The transfer of Chief Justice Vijaya K. Tahilramani from the Madras High Court, one of the bigger High Courts, to Meghalaya, one of the smallest High Courts in India sparked controversy and prompted her resignation.

- ‘Kin syndrome’:

- It is a term coined by Js. V.R Krishna Iyer to refer to the nepotism and personal patronage prevalent in the functioning of the Collegium System. Various reports have supported this view, stating that the whole judiciary is run by just a few hundred privileged families.

- No fixed timeline:

- There is no time limit fixed for the government to take actions on the collegium recommendations. This is the reason that appointment of judges takes a long time.

- Pendency:

- The system has proved inefficient and slow, resulting in huge number of vacancies in the judiciary and subsequently leading to pendency of cases.

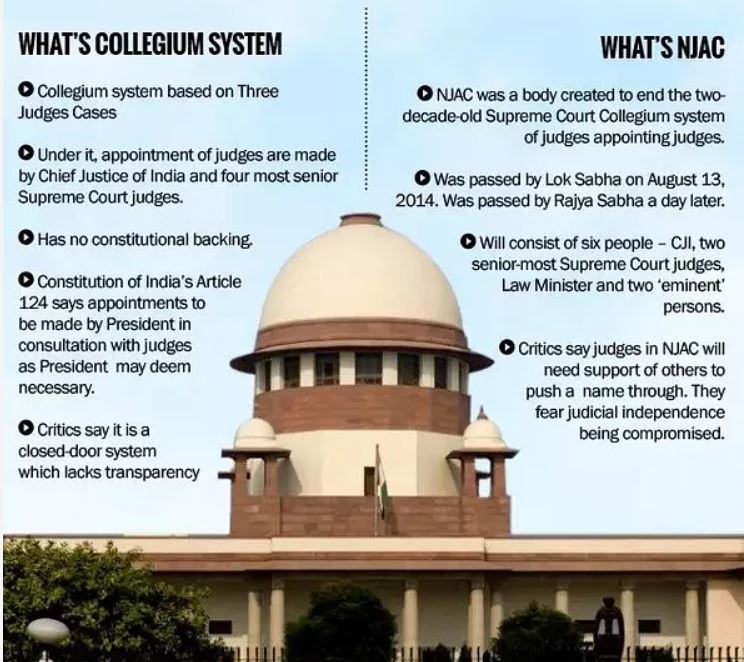

NATIONAL JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION (NJAC):

- Over the decades, several high-level Commissions, such as the Law Commission (1987), NCRWC (2002), National Advisory Council (2005) and 2nd Administrative Reforms Commission (2007) have examined the collegium method and suggested that an independent body be set up to make recommendations for appointments to the higher judiciary.

- In 2014, government introduced the NJAC through the 99th constitutional amendment act. Alongside, the Parliament also passed the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act, 2014, to regulate the NJAC’s functions.

- The NJAC Act and the Constitutional Amendment Act came into force from April 13, 2015.

- However, in October 2015, a Constitution bench of the Supreme Court struck down the Act by 4:1 majority, holding it as unconstitutional.

- The court viewed that the involvement of the executive in the appointment of judges impinged upon the primacy and supremacy of the judiciary, and violated the principle of separation of powers between the executive and judiciary which formed part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

FEATURES OF NJAC:

- The Act replaced the collegium system. Articles 124A, 124B and 124C were added to the Constitution to make the NJAC valid.

- It was a six-member body, comprising of:

- CJI as chairperson

- Two senior-most Supreme Court judges

- The Union law minister; and

- Two eminent persons, to be selected by a committee comprising the CJI, Prime Minister and leader of the opposition.

ARGUMENTS FAVORING THE NJAC ACT:

- Procedure established by law:

- The NJAC was established by the Parliament by amending the Constitution. Hence, the second judges’ case that created the collegium is irrelevant because the Constitution is now different from what it was back then.

- Historical backing:

- During the making of the constitution, Dr. Ambedkar had advocated for the executive’s participation in judicial appointments. Even the earlier drafts of the constitution presented in the constituent assembly had suggested that a panel be appointed to oversee the appointments process.

- In line with other countries:

- In no country do serving judges exclusively select and appoint judges. In all other major democracies, the elected members have a say in judicial appointments.

- Eg: In the United States, the Executive (the President) has the power to appoint but “by and with the advice and consent” of the Legislature (the Senate).

- Strengthen checks and balances:

- The government argued that the NJAC restores the constitutional mandate of checks and balances which was lost since the second Judges case.

- Eg: The presence of members outside the judiciary will ensure that chances of nepotism and favoritism in selections is reduced.

- Improve public trust:

- Erosion of credibility of the judiciary in the public mind, for whatever reasons, is a threat to the independence of the judiciary. The introduction of an independent commission can help remove the shroud of doubt over fair judicial appointments and thereby help reassure public trust in the institution.

ARGUMENTS OPPOSING THE NJAC ACT:

- Violation of basic structure:

- The right to appointment of judges lay at the core of the independence of the judiciary and forms a part of the basic structure of the Constitution. But the presence of three non-judicial members (the law minister and two eminent persons) would erode the independence of the judiciary.

- Involvement of ‘Eminent person’:

- The act neither defines who an ‘eminent person’ is nor does it mention the qualifications necessary for them. Hence, even persons with no judicial background can be appointed. But they will have strong influence in the decision making, which is unsustainable in the scheme of independence of the judiciary.

- Indirect veto power:

- The 3 non-judicial members together hold a virtual veto against the decisions of the judges. Thus, the government can potentially use this to affect the working of the commission.

WAY FORWARD:

Until a better mechanism is evolved, the Supreme court has to take steps to make collegium more transparent and accountable. This requires a major re-engineering of the existing process of appointment, like:

- Wider zone of consideration: In respect of appointments, the “zone of consideration” must be expanded to avoid criticism that many appointees hail from families of retired judges.

- Disclosure of reasons behind transfers: Full disclosure of reasons for transfer of judges should be made so as to eliminate public controversies.

- Making publishing mandatory: The voluntary exercise of publishing its various decisions and reasons can be made mandatory. For this, the court may make changes in its rules or, if needed, instruct the government to make laws deeming the same.

- All India Judicial Service: The AIJS should be introduced in order to attract the young talent to the judiciary and fill vacancies in the lowest levels.

However, in order to make the democratic principle of institutional checks and balances to succeed, it is desirable and essential to involve representatives of the people in the appointment process of judges. To satisfy the same, an independent appointment commission is the ideal choice.

But the government should not get a complete say in the selection process as was set out in the NJAC. Hence, unlike its predecessor, a new NJAC needs to ensure that while it puts in place a non-corrupt, efficient way of appointing judges, it is not seen as interfering in the working of the judiciary.

PRACTICE QUESTION:

Q. ‘The present system of judicial appointments in India exemplifies the misalignment between the core values of judicial independence and accountability’. Critically analyse?