Public Distribution System (PDS)

2021 OCT 28

Mains >

Economic Development > Indian Economy and issues > Public distribution system

WHY IN NEWS?

- Small cooking gas cylinders could soon be available for retail purchase at ration shop, as the Centre is coordinating with States and oil companies on the plan. This is part of a wider initiative to boost the financial viability of these shops, which are the backbone of the public distribution system.

NEED FOR PDS:

- Ensure food and nutritional security:

- It is needed to ensure food and nutritional security of the nation.

- Structural imbalances in the economy:

- Rising capital intensity, lack of land reforms, failure of poverty alleviation programmes, growing disparity between towns and villages >> makes PDS inevitable

- To ensure agriculture sector growth:

- If consumption of the poor does not increase there would be serious demand constraints on agriculture and could make the growth target of 4.5% per annum unachievable.

- Check food inflation:

- It has helped in stabilising food prices and making food available to the poor at affordable prices.

- Prevalence of hunger in India:

- As per FAO report in 2020 >>14% of population in India are under-nourished >> which makes an efficient PDS inevitable.

- To maintain buffer stock:

- It maintains the buffer stock of food grains in the warehouse so that the flow of food remains active even during the period of less agricultural food production, event of disasters, war etc.

- Re-distribution of food grains

- It has helped in redistribution of grains by supplying food from surplus regions of the country to deficient regions.

- Increased food production:

- The system of minimum support price and procurement has contributed to the increase in food grain production.

- To ensure self-sufficiency:

- PDS is needed to ensure micro level a macro level self-sufficiency by making food and other essentials available, accessible and affordable for all.

STATISTICS:

- Huge network of PDS:

- There are 5.32 lakh ration shops which distributes subsidised foodgrains to the 80 crore beneficiaries covered by the National Food Security Act.

- According to FAO estimates in ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, 2020 report:

- 189.2 million people (14% of total population) are undernourished in India

- 51% of women in reproductive age between 15 to 49 years are anaemic.

- As per Global Hunger Index 2021:

- India ranks 101 out of 116 countries

- The share of wasting among children in India rose from 17.1 per cent between 1998-2002 to 17.3 per cent between 2016-2020

- Fourth round of NFHS, conducted in 2015-2016, found that

- Prevalence of underweight, stunted and wasted children under five was at 35.7, 38.4 and 21.0 per cent.

- Studies reveal that India loses up to 4 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP) and up to 8 per cent of its productivity due to child malnutrition.

EVOLUTION OF PDS:

- PDS was introduced around World War II as a war-time rationing measure. Before the 1960s, distribution through PDS was generally dependant on imports of food grains.

- It was expanded in the 1960s as a response to the food shortages of the time; subsequently, the government set up the Agriculture Prices Commission and the FCI to improve domestic procurement and storage of food grains for PDS.

- By the 1970s, PDS had evolved into a universal scheme for the distribution of subsidised food

- Revamped Public Distribution System (RPDS):

- Till 1992, PDS was a general entitlement scheme for all consumers without any specific target.

- The Revamped Public Distribution System (RPDS) was launched in 1992 with a view to strengthen and streamline the PDS as well as to improve its reach in the far-flung, hilly, remote and inaccessible areas where a substantial section of the underprivileged classes lives.

- Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS):

- In 1997, the Government of India launched the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) with a focus on the poor.

- Under TPDS, beneficiaries were divided into two categories: Households below the poverty line or BPL; and Households above the poverty line or APL.

- Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY):

- AAY was a step in the direction of making TPDS aim at reducing hunger among the poorest segments of the BPL population.

- A National Sample Survey exercise pointed towards the fact that about 5% of the total population in the country sleeps without two square meals a day.

- In order to make TPDS more focused and targeted towards this category of population, the "Antyodaya Anna Yojana” (AAY) was launched in 2000 for one crore poorest of the poor families.

- National Food Security Act:

- In 2013, Parliament enacted the National Food Security Act.

- The Act relies largely on the existing TPDS to deliver food grains as legal entitlements to poor households. This marks a shift by making the right to food a justiciable right.

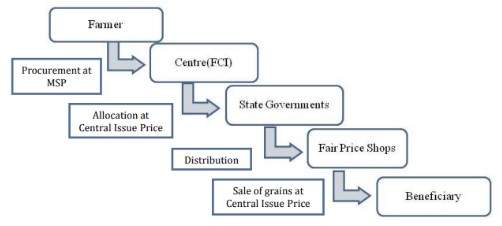

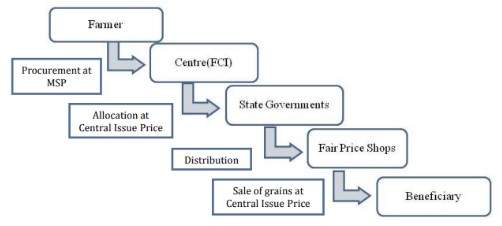

FUNCTIONING

- The Central and State Governments share responsibilities in order to provide food grains to the identified beneficiaries.

- The centre procures food grains from farmers at a minimum support price (MSP) and sells it to states at central issue prices.

- It is responsible for transporting the grains to godowns in each state.

- States bear the responsibility of transporting food grains from these godowns to each fair price shop (ration shop), where the beneficiary buys the food grains at the lower central issue price.

- Many states further subsidise the price of food grains before selling it to beneficiaries.

LIMITATIONS

|

What is open-ended procurement policy?

Under the open-ended procurement policy, the Centre extends price support to paddy and wheat through the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and the State agencies.

The wheat and paddy offered by farmers, within the stipulated period and conforming to the specifications, are bought at the minimum support price by the agencies, including the FCI, for the central pool.

The aim of procurement is to ensure that farmers get remunerative prices and do not resort to distress sale.

It is also meant for supplies to the poor under the National Food Security Act and other welfare schemes and for building up buffer stocks to ensure food security.

|

-

- Problem of ‘open ended procurement’:

- Due to open procurement policy >> Centre has been sitting on huge stockpiles of wheat and rice, far more than what is required annually for distribution under the Public Distribution System (PDS).

- This policy has led to mounting food stocks and adversely affected crop diversification.

- Data shows that annually 78-80 million tonnes of wheat and rice is procured for the central pool, against a requirement of 50-54 million tonnes for PDS, leaving the rest in excess.

- These excess stocks create storage problems and high storage and financing costs, leading to a high food subsidy burden

- According to data from the Food Corporation of India, India’s food grain stocks as on December 1, 2020 were estimated to be 52.29 million tonnes, almost 144 per cent beyond the quantity that would be needed

- Significant spike in food subsidy:

- CACP said that the economic cost of wheat has increased by about 31.3 per cent, from Rs 1,908 per quintal in 2013-14 to Rs 2,506 per quintal in 2019-20.

- On the other hand, the Central Issue Price (CIP) of wheat (the price at which wheat is sold through ration shops) has remained unchanged at Rs 200 per quintal since 2013, leading to a significant spike in food subsidy.

- Food subsidy burden has risen from Rs 92,000 crore in 2013-14 to Rs 1,84,220 crore in 2019-20 according to CACP.

- Change in consumption not reflected in procurement policy:

- Consumption pattern is gradually shifting from cereals to other protein rich products but procurement still focus on cereals.

- ‘Procurement gap’

- Benefiting rich farmers only:

- As per data of Committee on Restructuring of FCI (or Shanta Kumar committee) >> only 6% of Indian farmers benefit from minimum support prices (MSP).

- Regional inequalities:

- In the last two years, close to 45% of all the rice and wheat procured by government agencies came from just two States - Punjab (28.9%) and Haryana (15.9%).

- In FY19, government agencies procured more than 75% of all the rice and wheat produced in Punjab and Haryana. But in case of U.P it is below 20%.

- Issues with FCI:

- No pro-active liquidation policy

- One of the key challenges for FCI has been to carry buffer stocks way in excess of buffer stocking norms. During the last five years, on an average, buffer stocks with FCI have been more than double the buffer stocking norms.

- Poor financial health

- FCI had an outstanding loan of around Rs 2.54 trillion from the National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) as on 2020.

- Higher costs of labour

- Flawed incentive system in FCI depots for departmental workers

- Over reliance on departmental workers over cheap contract labours

- Use of proxy labour

- Lack of access to procurement

- Most of the farmers do not have access to procurement centres, as it is located in selective locations away from the farm gate.

- Negative externalities

- The over-emphasis on attaining self-sufficiency and a surplus in food grains, which are water-intensive, has been found to be environmentally unsustainable.

- Procuring states such as Punjab and Haryana are under environmental stress, including rapid groundwater depletion, deteriorating soil and water conditions from overuse of fertilisers.

- In storage:

- A performance audit by the CAG has revealed a serious shortfall in the government's storage capacity

- Less number of public warehouses >> excessive storage >> leading to wastage of food grains

- Poor condition of storage facility - Lack of cold storage etc.

- Lack of private participation in operation of storage facilities

- In distribution:

- Challenge of identification of beneficiaries:

- Exclusion and inclusion errors:

- 46% of food grains distributed through PDS does not reach beneficiaries (NSSO data)

- Reluctance:

- People’s reluctant to be identified due to fear of state surveillance

- Threat of violation of privacy:

- Intrusive state mechanism to identify the beneficiaries for welfare delivery often violates people’s right to privacy

- Judicial intervention further delays the process of identification

- Lack of proper poverty measurement:

- An expert group of the Ministry of Rural Development on the methodology for conducting the BPL census found that about 61% of the eligible population was excluded from the BPL list while 25% of non-poor households were included in the BPL list.

- Multi-dimensionality of backwardness owing to socio-economic conditions in India

- Challenges of household- individual connection:

- Recipient of subsidised food may have different priorities from intended beneficiaries. Thus food distribution at household level may not reach vulnerable sections like children, women, old age people etc.

- Lack of coordination between different departments

- Market distortion:

- Government intervention through food subsidies distort the market mechanism >> result in misallocation of resources >> lowers aggregate productivity >> disproportionately hurts the poor.

- Ex: High MSP >> excess cultivation of wheat and rice >> neglect of non-MSP products >> high price for non-MSP products >> hurts poor

- Leakages and diversion

- TPDS suffers from leakages in two ways - transportation leakages and black marketing by FPS owners.

- Dual pricing introduced through the TPDS incentives stakeholders to divert commodities into the open market where they can command a higher price.

- Bogus beneficiaries

- For example: Odisha has over two lakh ghost beneficiaries under the Public Distribution System (PDS), according to an RTI query in 2021.

- Issues with fair price shops:

- Lack of viability of FPS due to low margins

- Lack of monitoring to ensure timely opening

- Low off-take of food grains from FPSs by each household

- Lack of transparency in the selection of procedure of PDS dealers

- Lack of coverage:

- Remote areas such as hilly regions have less accessibility infrastructure.

- For example: the state of Arunachal Pradesh does not have a civil supplies corporation to manage the movement of foodgrains from the Food Corporation of India (FCI) godowns to Fair Price Shops (FPS).

- The FCI does not have its own godowns in the state either

REVAMPING

- 'One Nation One Ration Card'

- It seeks to provide nation-wide portability of National Food Security Act benefits i.e. a beneficiary will be able to buy subsidized food grains from any fair price shop across the country.

- However, for availing the benefits, linking of ration cards with their Aadhaar card is mandatory.

- An Integrated Management of PDS (IM-PDS) portal provides the technological platform for inter-state portability of ration cards, while Annavitran portal provides intra state portability (i.e inter and intra district).

- Biometric authentication and electronic Point of Sale (ePoS) devices installed at the Fair price shops will be used to identify the beneficiaries.

- Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Ann Yojana

- It seeks to provide free resources of 5 kg wheat or rice and 1 kg of preferred pulses for 80 crore poor people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The scheme was initially launched for three months in March 2020 and later extended till November 2020.

- Cleaning up of bogus beneficiaries:

- 4.39 crore bogus ration cards weeded out during the period 2013 to 2020 for rightful targeting of beneficiaries under NFSA

- Reforms in FCI

- ‘Depot Online’ system:

- To bring all operations of FCI Godowns online and to check reported leakage, ‘Depot Online’ system was initiated in all the FCI-Owned Depots.

- Open Market Sale Scheme

- Under this Government of India approved sale of wheat and rice available in central pool above the stocking norms

- Private Entrepreneur Guarantee Scheme (PEG)

- It aims for construction of storage godowns in Public Private Partnership (PPP) mode through private entrepreneurs, Central Warehousing Corporation (CWC) and State Warehousing Corporations (SWCs) to overcome storage constraints and ensure safe stocking of foodgrains across the country

- Reforms in Warehousing Development and Regulatory Authority (WDRA)

- Creation of IT platform and rewriting of rules and procedures has been initiated to streamline the warehousing sector.

- Computerization of PDS – ‘End to End Computerization’

- The project aims at improving operational efficiency, co-ordination, accessibility, speed in administration and to set Information Communication Technology (ICT) infrastructure

- PDS computerization has four phases:

- Phase1: Digitization of beneficiaries & other databases.

- Creation of data base of all storage warehouse in the State and PDS Centres, addresses of PDS agencies and all Fair Price Shops

- Phase 2: Digitization of Family wise and category wise ration cards (All APL, BPL, Antodya)

- Creation of Beneficiary Data and hosting the same thereof on State PDS information Portal.

- Issuance or modification or deletion of ration cards will be undertaken using software.

- In 2016 >> digitisation of 100 % of ration cards have been completed across the country.

- More than half of ration cards have been linked with Aadhaar cards

- Point of Sale Devices, to keep electronic record of allocation to the beneficiaries, have been installed in over 77,000 ration shops.

- These measures will help making PDS more transparent and leak proof

- It allows for online entry and verification of beneficiary data, online storing of monthly entitlement of beneficiaries, number of dependants, offtake of food grains by beneficiaries from FPS, etc.

- Phase 3: Computerization of supply chain management

- Online allocation of food grains will be done based on number of ration cards taken from software on real time basis.

- Management of stock in warehouse & movement activities will be done using software.

- Use of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology to track movement of trucks carrying food grains from state depots to FPS

- Food grains receipt and issuance will be entered online at State level warehouse where stock position of warehouse w.r.t. food grains will be available online.

- SMS alerts will be sent to beneficiaries regarding dispatch of commodities and receipt at FPSs.

- Phase 4: Transparency Portal

- Facility for beneficiaries to register their grievances on State PDS portal and view status thereof.

- Stakeholder details (Fair Price Shops, Storage warehouse / depots) will be available for public access.

- FPS wise monthly allocation, monthly lifting & monthly distribution of food grains under TPDS schemes will be available for public access

SUGGESTIONS:

- Enhance the fiscal health of ration shops

- Provide financial services through the ration shops.

- MUDRA loans, meant for small entrepreneurs, could also be extended to FPS dealers for capital augmentation.

- Review open-ended procurement policy:

- As recommended by Commission for Agricultural Costs and Price (CACP) Centre Government should review open-ended procurement of wheat and rice

- Adoption of recommendations of Shanta Kumar committee:

- ‘Limited procurement’ instead of ‘open procurement’:

- FCI should hand over all procurement operations of wheat, paddy and rice to states that have gained sufficient experience in this regard

- FCI will accept only the surplus (after deducting the needs of the states under NFSA) from these state governments (not millers) to be moved to deficit states

- FCI should move on to help those states where farmers suffer from distress sales at prices much below MSP, and which are dominated by small holdings, like Eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam etc

- DFPD/FCI at the Centre should enter into an agreement with states before every procurement season regarding costing norms and basic rules for procurement.

- Three issues are critical to be streamlined to bring rationality in procurement operations and bringing back private sector in competition with state agencies in grain procurement

- (a) Centre should make it clear to states that in case of any bonus being given by them on top of MSP, Centre will not accept grains under the central pool beyond the quantity needed by the state for its own PDS

- (b) The statutory levies including commissions, which vary from less than 2 percent in Gujarat and West Bengal to 14.5 percent in Punjab, need to be brought down uniformly to 3 percent.

- (c) Quality checks in procurement have to be adhered to, and anything below the specified quality will not be acceptable under central pool

- Revisit MSP policy:

- Currently, MSPs are announced for 23 commodities, but effectively price support operates primarily in wheat and rice and that too in selected states.

- This creates highly skewed incentive structures in favour of wheat and rice.

- While country is short of pulses and oilseeds (edible oils), their prices often go below MSP without any effective price support.

- Further, trade policy works independently of MSP policy, and many a times, imports of pulses come at prices much below their MSP. This hampers diversification.

- Therefore the committee recommends that pulses and oilseeds deserve priority and GoI must provide better price support operations for them, and dovetail their MSP policy with trade policy so that their landed costs are not below their MSP.

- Promotion of Negotiable warehouse receipt system (NWRs)

- Under this system, farmers can deposit their produce to the registered warehouses, and get say 80 percent advance from banks against their produce valued at MSP.

- They can sell later when they feel prices are good for them. This will bring back the private sector, reduce massively the costs of storage to the government, and be more compatible with a market economy.

- Government of India through FCI and Warehousing Development Regulatory Authority (WDRA) can encourage building of these warehouses with better technology, and keep an on-line track of grain stocks with them on daily/weekly basis.

- In due course, Government can explore whether this system can be used to compensate the farmers in case of market prices falling below MSP without physically handling large quantities of grain.

- On National Food Security Act

- Coverage of NFSA need to be brought down from 67% to 40%

- On central issue prices, committee recommends that pricing for priority households must be linked to MSP, say 50 percent of MSP.

- Targeted beneficiaries under NFSA should be given 6 months ration immediately after the procurement season ends. This will save the consumers from various hassles of monthly arrivals at FPS and also save on the storage costs of agencies. Consumers can be given well designed bins at highly subsidized rates to keep the rations safely in their homes.

- Cash transfers in PDS

- Committee recommends gradual introduction of cash transfers in PDS, starting with large cities

- This will be much more cost effective way to help the poor, without much distortion in the production basket, and in line with best international practices.

- Committee calculations reveal that it can save the exchequer more than Rs 30,000 crores annually

- On stocking and movement related issues

- FCI should outsource its stocking operations to various agencies such as Central Warehousing Corporation, State Warehousing Corporation, Private Sector under Private Entrepreneur Guarantee (PEG) scheme

- It should be done on competitive bidding basis, inviting various stakeholders and creating competition to bring down costs of storage.

- India needs more bulk handling facilities than it currently has. Many of FCI's old conventional storages that have existed for long number of years can be converted to silos with the help of private sector and other stocking agencies.

- Better mechanization is needed in all silos as well as conventional storages.

- Covered and plinth (CAP) storage should be gradually phased out with no grain stocks remaining in CAP for more than 3 months.

- Silo bag technology and conventional storages where ever possible should replace CAP.

- Movement of grains needs to be gradually containerized which will help reduce transit losses, and have faster turn-around-time by having more mechanized facilities at railway sidings.

- On Buffer Stocking Operations and Liquidation Policy:

- FCI have to work in tandem to liquidate stocks in Open Market Sale Scheme (OMSS) or in export markets, whenever stocks go beyond the buffer stock norms.

- The current system is extremely ad-hoc, slow and costs the nation heavily. A transparent liquidation policy is the need of hour, which should automatically kick-in when FCI is faced with surplus stocks than buffer norms.

- On Labour Related Issues:

- Condition of contract labour at FCI depots should be improved by giving them better facilities.

- FCI depots should be mechanized so that reliance on departmental labour can be reduced

- On direct subsidy to farmers

- Committee recommends that farmers be given direct cash subsidy and fertilizer sector can then be deregulated.

- This would help plug diversion of urea to non-agricultural uses as well as to neighbouring countries, and help raise the efficiency of fertilizer use.

- On end to end computerization

- Committee recommends total end to end computerization of the entire food management system, starting from procurement from farmers, to stocking, movement and finally distribution through TPDS.

- Some states have done a commendable job on computerizing the procurement operations.

- But its dovetailing with movement and distribution in TPDS has been a weak link, and that is where much of the diversions take place.

- On the new face of FCI

- The new face of FCI should be akin to an agency for innovations in Food Management System with a primary focus to create competition in every segment of foograin supply chain, from procurement to stocking to movement and finally distribution in TPDS, so that overall costs of the system are substantially reduced, leakages plugged, and it serves larger number of farmers and consumers.

- In this endeavour FCI should:

- Make itself much leaner and nimble -with scaled down/abolished zonal offices

- Focus on eastern states for procurement

- Upgrade the entire grain supply chain towards bulk handling

- End to end computerization

- Bringing in investments, and technical and managerial expertise from the private sector.

- Take more business oriented approach with a pro-active liquidation policy to liquidate stocks in OMSS/export markets, whenever actual buffer stocks exceed the norms.

- Tackling inclusion and exclusion error in beneficiary identification:

- This can be done through Aadhaar seeding, detection of ineligible/bogus ration cards, de-duplication of digitised data etc.

- Improve the nutritional value of food provided through PDS:

- Bio-fortified foods need to be distributed through the PDS

- Inclusion of millets – these are relatively cheaper but high on nutrition

- Adoption of Justice Wadhwa Committee recommendation:

- The Justice Wadhwa Committee Report for PDS (2011) recommended end to end computerisation of PDS to prevent diversion and to enable secure identification at ration shops.

- Alternative systems:

- Food coupons

- Household is given the freedom to choose where it buys food

- Increases incentive for competitive prices and assured quality of food grains among PDS stores

- Ration shops get full food grains from the poor, no incentive to turn the poor away

- Cash transfers

- Cash in the hands of poor increases their choicess

- Administrative costs of cash transfer programmes may be significantly lesser than that of TPDS

- Increased public participation

- Ensure Increased public participation through social audits and participation of SHGs, Cooperatives and NGOs in ensuring the transparency of PDS system at ground level.

- Role of Aadhaar:

- Integrating Aadhar with TPDS will help in better identification of beneficiaries and address the problem of inclusion and exclusion errors.

BEST PRACTICE:

- Arun ePDS initiative in Arunachal Pradesh

- The practical challenges of implementing the Public Distribution System (PDS) in Arunachal Pradesh led to the conceptualisation of the Arun ePDS initiative to improve delivery through process re-engineering and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs).

- Arun ePDS is a dynamic scheme and tackles extreme challenges of connectivity, both physical as well as virtual.

- It facilitates citizen-centric functioning and rapid grievance redressal, have centralised reporting and monitoring, create efficient allocation of commodities, and track supply chain from FCI godowns to FPS.

- Universal PDS of Tamil Nadu:

- Tamil Nadu implements a universal PDS, such that every household is entitled to subsidised food grains. This way, exclusion errors are reduced.???????

PRACTICE QUESTION:

Q. “Excessive stock on one hand and severe malnutrition on the other reflects the failure of our public distribution system”. Do you agree with this statement? Discuss.