Tribunal Reforms In India

2021 NOV 25

Mains >

Polity > Judiciary > Tribunals

WHY IN NEWS?

- The Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021 proposing changes in the constitution processes of a tribunal has become a subject of controversy since it was passed on August 13, 2021

INTRODUCTION

- Tribunals are judicial or quasi-judicial institutions established by law.

- The objective may be to reduce case load of the judiciary or to bring in subject expertise for technical matters.

- The Supreme Court has ruled that tribunals, being quasi-judicial bodies, should have the same level of independence from the executive as the judiciary. Key factors include the mode of selection of members, the composition of tribunals, and the terms and tenure of service.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS REGARDING TRIBUNALS

- The original Constitution did not contain provisions with respect to tribunals.

- The 42nd Amendment Act of 1976 added a new Part XIV-A to the Constitution entitled as ‘Tribunals’. It consists of two Articles:

- Article 323 A:

- It deals with administrative tribunals

- It empowers the Parliament to provide for the establishment of administrative tribunals for the adjudication of disputes relating to recruitment and conditions of service of persons appointed to public services of the Centre, the states, local bodies, public corporations and other public authorities.

- In pursuance of Article 323 A, the Parliament has passed the Administrative Tribunals Act in 1985. The act authorises the Central government to establish one Central administrative tribunal and the state administrative tribunals. This act opened a new chapter in the sphere of providing speedy and inexpensive justice to the aggrieved public servants.

- Article 323 B:

- It deals with tribunals for other matters, such as labour reforms, taxation and ceiling on urban property.

- Here, both the Parliament and the state legislatures are authorized to provide for the establishment of tribunals for the adjudication of disputes.

- In 2010, the Supreme Court clarified that the subject matters under Article 323B are not exclusive, and legislatures are empowered to create tribunals on any subject matters under their purview as specified in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution

- In Chandra Kumar case (1997), the Supreme Court declared those provisions of these two articles which excluded the jurisdiction of the high courts and the Supreme Court as unconstitutional. Hence, the judicial remedies are now available against the orders of these tribunals.

EVOLUTION TRIBUNAL SYSTEM IN INDIA

- The tribunal system has developed as a parallel to the traditional court system over the last eighty years.

- In 1941:

- The Income Tax Appellate Tribunal was established as the first Tribunal in India.

- The objective was to reduce the workload of courts, expedite adjudication of disputes, and build expertise on tax matters within the Tribunal

- In 1969

- The First Administrative Reforms Commission recommended that the central government should set up Civil Services Tribunals at the national level and state levels.

- In 1974

- The Sixth Law Commission (1974), recommend setting up a separate high-powered tribunal and commission for adjudication of matters in High Courts.

- This was aimed at reducing arrears of cases in the High Courts

- In 1976

- The Swaran Singh Committee (1976) noted that the High Courts were burdened with service cases by public servants.

- It recommended setting up: (i) administrative tribunals (both at national level and state level) to adjudicate on matters related to service conditions, (ii) an all-India Appellate Tribunal for matters from labour courts and industrial tribunals, and (iii) tribunals for deciding matters related to various sectors (such as revenue, land reforms, and essential commodities).

- It further recommended that the decisions of the tribunals should be subject to scrutiny by the Supreme Court

- In 1976:

- The 42nd amendment to the Constitution was passed. It added a new Part XIV-A to the Constitution entitled as ‘Tribunals’.

- Since the 1980s:

- Several tribunals were established under different Acts.

- These include the Central Administrative Tribunal, Securities Appellate Tribunal, Film Certification Appellate Tribunal, Armed Forces Tribunal, National Green Tribunal, Industrial Tribunal etc.

- In 2017:

- The Finance Act, 2017 reorganised the tribunal system by merging tribunals based on functional similarity.

- The number of Tribunals was reduced from 26 to 19.

- It delegated powers to the central government to make Rules to provide for the qualifications, appointments, removal, and conditions of service for chairpersons and members of these tribunals.

- In 2021:

- Tribunals Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Act, 2021 was passed.

- They abolish nine tribunals and transfer their functions to existing judicial bodies (mainly High Courts).

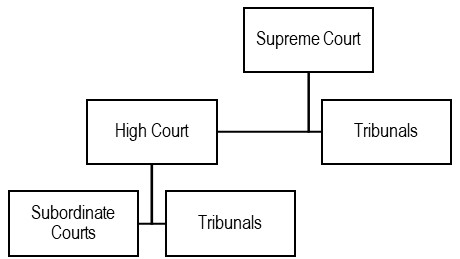

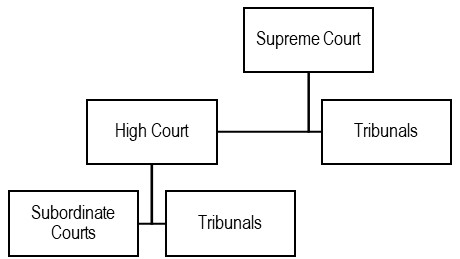

STRUCTURE OF INDIAN TRIBUNAL SYSTEM:

- Currently, tribunals have been created both as substitutes to High Courts and as subordinate to High Courts (see figure)

- In the former case, appeals from the decisions of Tribunals (such as the Securities Appellate Tribunal) lie directly with the Supreme Court.

- In the latter case (such as the Appellate Board under the Copyright Act, 1957), appeals are heard by the corresponding High Court.

NEED FOR TRIBUNALISATION OF JUSTICE:

- Reduce load on ordinary courts:

- The traditional system has been overburdened with ordinary suits.

- Their procedures are formalistic, expensive and took years to resolve. The tribunal system gives the much-needed relief to such ordinary courts.

- Specialized approach:

- Tribunals comprise of people who have spent a considerable amount of time on one particular subject or field of knowledge.

- Hence, they are in a better position to understand technical issues and ensure justice.

- Flexibility:

- The introduction of administrative tribunals engendered flexibility and versatility in the judicial system of India.

- Unlike the procedures of the ordinary court which are stringent and inflexible, the administrative tribunals have a quite informal and easy-going procedure.

- Cheaper resolution:

- Because of its flexibility and informality, the complaints need not be represented by a lawyer.

- They may be represented by an individual or by themselves. They have few operational formalities. Hence, tribunals ensure inexpensive justice.

- Timely justice:

- Tribunals follow the principle of natural justice and the procedures are much simpler compared to courts.

- Also, most tribunals have time limits within which they should dispose cases.

- Quality Justice:

- Given the ever-increasing complexity of today’s disputes, the administrative tribunals are among the most effective method of providing adequate and quality justice in less time.

CRITICISM OF TRIBUNALS:

- Against the Rule of Law:

- Rule of law promotes equality before the law and supremacy of ordinary law over the arbitrary functioning of the government.

- The tribunals somewhere restrict the ambit of the rule of law by providing separate laws and procedures for certain matters.

- Lack of specified procedure:

- The administrative adjudicatory bodies do not have any rigid set of rules and procedures. Thus, there is a chance of violation of the principle of natural justice and scope for arbitrariness.

- Absence of legal expertise:

- Members of the administrative tribunals may be experts of different fields but not essentially trained in judicial work. Therefore, they may lack the required legal expertise which is an indispensable part of resolving disputes.

- Pendency of cases

- One of the key purposes of tribunals is to reduce the workload of courts, so that there is quicker disposal of cases.

- However, even some tribunals face the issue of a large backlog of cases.

- For example: As of March 2021

- The central government industrial tribunal cum-labour courts had 7,312 pending cases

- Armed Forces Tribunal had 18,829 pending cases

- Income-tax Appellate Tribunal had 91,643 pending cases

- Vacancy:

- The issue of vacancies is neither recent nor exclusive to the courts. Tribunals also suffer from the manpower shortage issues.

- The 74th Parliamentary Standing Committee Report expressed its concern about vacancies being a source of tribunal instability.

- At present, around 240 vacancies in 15 major tribunals are pending approval by the Central Government.

- No fresh appointments have been made in any tribunal since 2017.

- Absence of uniformity:

- There is a degree of variation in the appointment process, membership requirements, retirement age, finances, and the different tribunals facilities.

- These contradictions arise due to tribunals functioning under separate ministries.

- No reduction in burden:

- After the judgment in L. Chandrakumar case, the Supreme Court made it clear that appeals against tribunals shall lie only before the High Courts.

- This has only added another level of litigation and has not helped to reduce the burden on courts.

- Losing relevance:

- Since tribunals now serve as lower than High Courts, many states have considered it better to abolish them because now they would be redundant.

- Undue influence of executive in appointment:

- The Supreme Court accused central government of “cherry-picking” the candidates from the wait-list without exhausting the recommended list.

- Lack of autonomy:

- Tribunals are dependent on the executive for administrative requirements

- Ministries are often parties in front of the very tribunals whose workers, budgets, and administration they deal with.

- A revolving door between ministry bureaucracy and tribunal posts further questions the independence of tribunals.

- Issues with term of office:

- In 2019, the Supreme Court stated that a short tenure of members along with provisions of re-appointment increases the influence and control of the Executive over the judiciary.

- Moreover, in such short term of office, by the time the members achieve the required knowledge, expertise and efficiency, one term gets over.

- This prevents enhancement of adjudicatory experience, thereby, impacting the efficacy of tribunals.

- Centre is yet to constitute a National Tribunals Commission (NTC):

- The idea of an NTC was first mooted in L. Chandra Kumar v. Union of India (1997).

JUDICIAL INTERVENTIONS TO REFORM TRIBUNALS:

- S. P. Sampath Kumar case 1986

- It is constitutionally valid for Parliament to create an alternate institution to High Courts with jurisdiction over certain matters provided that the alternate body has same efficacy as that of the High Court.

- Such tribunals will be considered substitutes of the High Courts.

- Court held that appointments should be made either by

- Central government after consultation with the Chief Justice of India, or

- A high-powered selection committee headed by Judge of Supreme Court or High Court.

- L. Chandra Kumar case 1997

- A tribunal which substitutes High Courts as an alternative institutional mechanism for judicial review (to lessen the burden on High Courts) must have the status of High Courts.

- Such tribunals will act as courts of first instance in respect of areas of law for which they have been constituted. However, decisions of these tribunals will be subject to scrutiny by a division bench of the High Court within whose jurisdiction the concerned tribunal falls.

- For a tribunal substituting a High Court, any weightage in favour of non-judicial members would render the tribunal less effective and potent than the High Court.

- Only persons with judicial experience should be appointed to tribunals.

- To ensure uniformity in administration, a separate independent mechanism should be set up to manage the appointment and administration of tribunals. Until such an independent agency is set up, all tribunals should be under the administration of a single nodal Ministry (such as the Ministry of Law)

- R. Gandhi versus Union of India 2010:

- Parliament may create alternate mechanism to High Courts on subject matters in the Union List.

- There is no need of a technical member if jurisdiction of courts is transferred to the tribunals solely to achieve expeditious disposal of matters. In any bench, technical members must not outnumber judicial members.

- Only Secretary level officers with specialised knowledge and skills should be appointed as technical members.

- Madras Bar Association versus Union of India, 2014

- Administrative support for all tribunals should come the Ministry of Law and Justice.

- Neither the tribunals nor their members must seek or be provided with facilities from the respective parent Ministry or concerned Department.

- Rojer Mathew case 2019

- Judicial functions cannot be performed by technical members.

- Provisions to allow removal of judges by the Executive are unconstitutional.

- There should be a uniform age of retirement for all members of all the tribunals.

- Short tenures lead to control of executives over tribunals causing adverse effects on the independence of judiciary.

- The impact of amalgamation of tribunals should be analysed with judicial impact assessment.

- Madras Bar Association v/s Union of India (2020)

- National Tribunals Commission should be set up to supervise appointments, as well as functioning and administration of tribunals.

- Members will have a term of five years instead of four years.

- SC directed on the composition of a search-cum-selection committee and its role in disciplinary proceedings

- Madras Bar Association versus Union of India, 2021

- The Court struck down provisions related to the four-year tenure and minimum age requirement of 50 years for members in the Tribunals Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021.

SALIENT PROVISIONS OF TRIBUNAL REFORMS (RATIONALISATION AND CONDITIONS OF SERVICE) ACT:

- The Bill seeks to dissolve certain existing appellate bodies and transfer their functions (such as adjudication of appeals) to other existing judicial bodies

- For example:

- Functions of Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) under The Cinematograph Act, 1952 transferred to High Court

- Functions of Appellate Board under The Copyright Act, 1957 transferred to Commercial Court

- Amendments to the Finance Act, 2017:

- The Finance Act, 2017 merged tribunals based on domain.

- It also empowered the central government to notify rules on: (i) composition of search-cum-selection committees, (ii) qualifications of tribunal members, and (iii) their terms and conditions of service (such as their removal and salaries).

- The Act removes these provisions from the Finance Act, 2017.

- Provisions on the composition of selection committees, and term of office have been included in the Act.

- Qualification of members, and other terms and conditions of service will be notified by the central government.

- Search-cum-selection committees:

- The Chairperson and Members of the Tribunals will be appointed by the central government on the recommendation of a Search-cum-Selection Committee.

- The Committee will consist of:

- (i) The Chief Justice of India, or a Supreme Court Judge nominated by him, as the Chairperson (with casting vote)

- (ii) Two Secretaries nominated by the central government,

- (iii) The sitting or outgoing Chairperson, or a retired Supreme Court Judge, or a retired Chief Justice of a High Court

- (iv) The Secretary of the Ministry under which the Tribunal is constituted (with no voting right).

- State administrative tribunals will have separate search-cum-selection committees with Chief Justice of the High Court of the concerned state as the Chairman

- Eligibility and term of office:

- The Act provides for a four-year term of office (subject to the upper age limit of 70 years for the Chairperson, and 67 years for members).

- Further, it specifies a minimum age requirement of 50 years for appointment of a chairperson or a member.

CHALLENGES WITH THE ACT:

- Affect quick dispute resolution:

- For example: FCAT acted like a buffer for filmmakers, and decisions taken by the tribunal were quick >> Now filmmakers had no option but to approach the court to seek redressal against CBFC certifications

- The move to scrap FCAT is against the recommendations of Mudgal committee and Shyam Benegal committee

- Increases the burden of Court

- Centre has replaced Appellate authorities under nine laws (Cinematograph Act, Copyright Act, Trade Marks Act etc.) with High Courts or Civil Courts

- Lack of stakeholder consultation

- Violation of SC order in Rojer Mathew case of 2019:

- In this case, Supreme Court’s directed that judicial impact assessment need to be conducted prior abolishing the tribunals

- But no such impact assessment was carried out in this case

- Terms of members not as directed by SC in Madras Bar Association case (2020):

- The Act stipulated 4 year term instead of 5 years, as directed by Court

- Violate separation of power:

- As the central government has higher role in appointment and removal of tribunal members >> it violates the doctrine of separation of judiciary from executive.

WAY FORWARD

- Ensuring independence:

- The independence of tribunal on matters of the selection and removal of members, the recruitment of judges/bureaucrats and meeting infrastructure and financial requirements needs to be assured.

- Encourage uniformity:

- Uniformity among tribunals in matters of age of members, appointment, removal and the operating procedures should be developed.

- Nodal ministry:

- Administration of tribunals needs a single nodal authority or ministry to improve performance.

- The Supreme Court had recommended that all administrative matters be managed by the Ministry of Law and Justice rather than the ministry associated with the subject area

- Constitute a National Tribunals Commission (NTC)

- The Supreme Court in 2020 directed the Centre to constitute a National Tribunals Commission (NTC) as an independent umbrella body to:

- Supervise the functioning of tribunals

- Appointment of and disciplinary proceedings against members

- Take care of administrative and infrastructural needs of the tribunals

- Function as an independent recruitment body

- One of the main reasons for NTC is the need for an authority to support uniform administration across all tribunals.

- The NTC could therefore pave the way for the separation of the administrative and judicial functions carried out by various tribunals

BEST PRACTICE:

- United States of America:

- In the U.S, tribunals are empowered to exercise only quasi-judicial functions related to administrative actions.

- The country’s Constitution does not allow vesting judicial powers in a body which is not a court.

- The decisions of these administrative tribunals are subject to judicial review by courts having jurisdiction over them

- United Kingdom:

- United Kingdom has a two-tier tribunal system, which consists of: (i) a First Tier Tribunal, and (ii) an Upper Tribunal.

- The appeals against the First Tier Tribunal lie with the Upper Tribunal

- Appeals from the Upper Tribunal lie to the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal is the second highest court after the country’s Supreme Court.

PRACTICE QUESTION:

Q. Examine the need for a radical restructuring of the present tribunals system in India